James Akecheta sat slack in a metal chair, an infant dangling from his arm. In front of him was a small table. Every now and then, James would lean forward and reach for a little cup of espresso. He sipped slowly, squinting his eyes. The baby grasped at something far away and made noises.

James Akecheta sat slack in a metal chair, an infant dangling from his arm. In front of him was a small table. Every now and then, James would lean forward and reach for a little cup of espresso. He sipped slowly, squinting his eyes. The baby grasped at something far away and made noises.

After a time, James turned his wrist, palm up, and studied the hour on his watch. He made a face and sucked at the back of his lips. Then he looked at the baby and pressed on its nose with his finger and smiled. He said, “I guess it’s just you and me, kid.”

Just to be sure, he ordered another espresso. Again, he drank slowly and observed the flow of customers at the café. When he finished the second espresso he made eye contact with a waitress and let her know that he was ready to pay by signing an imaginary check in the air.

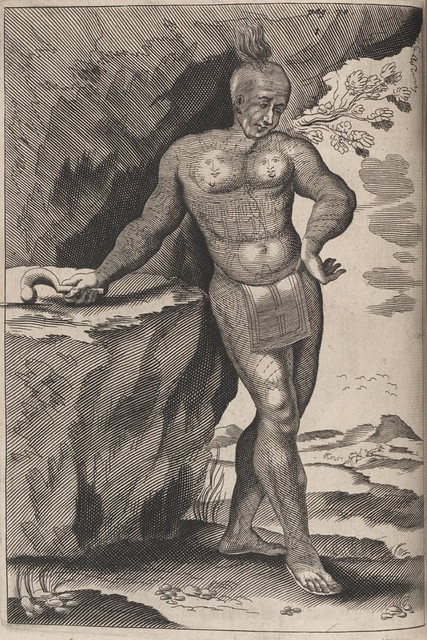

James was a big man—tall and muscular. He liked to showcase his arms by wearing cut-off shirts. His ex-wife used to say he looked like the kind of guy who was cut from stone. She complimented him on his voice, which was deep and husky. “It reminds me of honey,” she’d say. “Honey dripping from a spoon.”

The waitress dropped the check on the table and James fished in his pocket for change. The baby looked up at the waitress, sucking one of its hands.

“Cute kid,” said the waitress.

James looked her over. She wasn’t very attractive. “Thanks”, he said. “She’s my raison d’être.”

“What?” said the waitress, hand on hip.

James smoothed out two one-dollar bills on the table and weighted them down with a few quarters. “Thanks,” he said again, and got up to leave.

In reality, there were two James Akechetas. The one who went to work every night at the Crow Bar—a local watering hole frequented mostly by bikers and other rough-and-tumble types. The James who worked out at a gym called The Firm, where everybody called him Jimmy and asked to feel his biceps. James the barfly, the muscleman, the doperunner. A real badass. This was a shell, though—a sort of persona he’d created for himself.

During the day, when he wasn’t working, he liked to lounge in his back yard under the sun, splayed out on a lawn chair, reading French poetry (he preferred the Symbolists), sipping from an ice-cold glass of lemonade.

He lived alone and enjoyed the solitude. He liked to tinker around in the workshop he’d built next to the house, inventing projects for himself. Most of the furniture he’d made with his own hands.

For James, daylight hours were the best. Night meant work, having to see people and socialize, which he was good at but wasn’t keen on. Things were perfect until they were inevitably ruined by others.

Outside the air was hot and dry and the sun had just begun to scratch at the raw rocky mountaintops to the west. Everything stained blood red by the sunset. He looked again at the infant in his arms and sucked at his lips. He stood there in front of the café next to his truck for the better part of two minutes. Thinking. He looked back down at the baby in his arms and rubbed his nose to its. “Well here we are, sweetie,” he said. “Papa’s gotta meet with some friends of his.”

By the time he pulled into the bowling alley parking lot it was dark. The reflection of neon lights danced on the windshield of his truck.

He reached into the glovebox and grabbed his .357 and tucked it into the waistband of his jeans. He looked back at the baby. She was asleep in her carseat. He sucked at the back of his lips and pinched the bridge of his nose. “I’ll be right back, sugar, you just sit tight now.”

He climbed out of the truck and made his way toward the back of the bowling alley. As he walked he could feel the cold, smooth surface of the revolver.

When he rounded the corner he was met with three massive shadows. Then he was on the ground. The shadows kicked at his stomach, his back, his ribs. He could feel them crack and crunch under the blows.

“Where’s the ice, Jimmy?” one of them shouted.

“That was quite the inventory, Jimbo” said another.

A wave of black washed over him and he felt like he was dreaming. He remembered feeling like this before, when he was a kid, when he had pneumonia and hallucinated in bed with fever. A rush of voices. Songs he’d heard that day, people he’d spoken to. His dead mother. Fragments of Baudelaire and Rimbaud. His daughter. His baby daughter.

His baby daughter.

When he came to it was dark. He had come from darkness and arrived at another. It was musky and smelled like shit and metal. Someone had tossed him into a dumpster.

He could barely move. He reached for the weapon he’d shoved in his jeans but it wasn’t there. It took him half an hour to climb out.

When he did, dawn was breaking over the smaller, more distant mountains to the east. He limped and heaved his way back around the corner of the alley and into the gray light of the parking lot. A few vehicles dotted the space, but he didn’t see his truck. Then the pain was gone and his heart began to stomp and his guts went cold.